On paper, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) has already achieved what most states are still aiming for. Since 2020, the ACT has matched all of its electricity consumption with renewable generation, earning its reputation as Australia’s first 100% renewable jurisdiction. But unlike states with wind farms, dams, or solar hubs within their borders, the ACT’s clean energy story is largely built elsewhere.

The territory produces only a small fraction of the electricity it uses. Instead, it relies on long-term renewable energy contracts tied to wind and solar projects across New South Wales (NSW), Victoria (VIC), and South Australia (SA). Physically, the ACT remains fully dependent on the National Electricity Market (NEM), drawing power from the same grid as surrounding regions. What sets it apart is not how electricity flows, but how it is accounted for, funded, and secured.

This makes the ACT a different kind of case study. Its grid challenge is not about building generation or managing storage, but about proving whether policy-led decarbonisation can work without direct control over infrastructure.

In this instalment of our Electricity Grids: State by State series, we examine how the ACT went beyond 100% renewables on paper, what that means for grid reliability in practice, and where the limits of this model begin to show.

The current grid

The ACT does not operate its own standalone electricity system. Physically, it is embedded within NSW’s distribution and transmission network, drawing power from the same grid that supplies surrounding regions. Every electron flowing into homes and businesses in Canberra comes through the NEM.

Local generation plays only a minor role. Small-scale rooftop solar is widespread across Canberra’s suburbs and contributes meaningfully during the day, but utility-scale generation within ACT borders is limited by land availability and planning constraints. As a result, the territory relies almost entirely on imported electricity to meet demand in real time.

What makes the ACT different is how that electricity is sourced financially rather than physically. Through a series of long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), the ACT government has contracted renewable energy projects located across multiple states. These agreements guarantee that, over the course of a year, renewable generators produce at least as much electricity as the ACT consumes. The power itself enters the grid wherever it is generated, while the ACT receives the environmental and financial benefits through market settlement.

This means the ACT’s grid operation looks conventional on the surface, but it experiences the same price signals, congestion, and reliability risks as NSW. During heatwaves, calm weather, or transmission constraints, the ACT draws electricity from the same mix of generators as its neighbours. The difference lies in accounting.

In effect, the ACT has decoupled consumption from generation location. It remains fully dependent on the strength and stability of the broader NEM, even as it claims 100% renewable supply on an annual basis. That distinction underpins both the success of the ACT’s model and the questions it raises about how far policy-led renewable targets can go without direct control over the grid itself.

The challenge — accounting vs. physics

The ACT’s renewable success is real, but it exists within the rules of the market, not the laws of physics. While the territory matches its annual electricity use with renewable generation on paper, it cannot control when or where that power is produced. In real time, Canberra is exposed to the same constraints as the rest of the NEM.

Electricity flows according to availability. When the wind isn’t blowing at a contracted wind farm, or when solar output drops after sunset, the ACT still draws power from whatever generators are operating on the grid at that moment. That can include gas or coal, particularly during peak demand events or system stress. The renewable claim holds over a year, but it doesn’t insulate the territory from short-term reliability risks.

This creates a structural dependence. Because the ACT owns little generation and no transmission assets, it relies on NSW’s grid strength, interconnection, and dispatchable capacity to keep the lights on. If congestion builds, prices spike, or outages occur elsewhere in the system, the ACT feels those impacts immediately. Its renewable status does not confer physical priority or protection.

There is also a scaling challenge. The ACT’s model works partly because of its size. As a relatively small electricity consumer, it can contract renewable output without significantly distorting the broader market. If larger states attempted the same approach without building local infrastructure, the mismatch between paper claims and physical supply would become harder to manage.

In short, the ACT has proven that policy can decarbonise consumption, but it has not eliminated the need for firm generation, transmission, investment, or system-wide coordination. The challenge now is not maintaining the 100% figure, but understanding its limits in a grid that must still balance supply and demand every second.

The renewable expansion – Contracts over construction

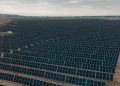

Unlike other jurisdictions, the ACT’s renewable expansion hasn’t involved a rush to build local infrastructure. Instead, it has focused on financing and underwriting renewable projects elsewhere in the market. Long-term power purchase agreements have been the main tool, providing revenue certainty to wind and solar farms across NSW, VIC, and SA.

These contracts have played a meaningful role in accelerating renewable investment beyond the ACT’s borders. By guaranteeing a fixed price over many years, they’ve helped projects reach financial close that may otherwise have stalled. In that sense, the ACT has acted as a catalyst rather than a host, using its demand to unlock supply where land, resources, and transmission already exist.

But this approach has limits. Because the ACT doesn’t control where generation connects to the grid, it has little influence over congestion, curtailment, or timing. If a contracted wind farm is producing power during a period of low demand or network constraint, the electricity may be curtailed even though the ACT is still “buying: it on paper. Likewise, the territory has no direct way to ensure that renewable output aligns with its own peak demand periods.

More recently, the ACT has begun looking beyond simple energy matching. Storage-linked contracts, firmed renewables, and demand-side initiatives are increasingly part of the conversation. These steps recognise that a system built entirely on annual accounting can only go so far before it runs up against real-time grid consents.

The ACT’s renewable expansion, then, is best understood as a market-led strategy rather than an engineering one. It has successfully driven investment and decarbonised consumption, but it relies on the broader grid to absorb, balance, and deliver that energy when it’s actually needed.

What it means for the future

The ACT’s model has proven that electricity consumption can be decarbonised without owning generation or transmission assets. By using long-term contracts, the territory has reduced emissions, supported renewable investment, and shielded itself from some wholesale price volatility. For a small jurisdiction, that approach has delivered clear results.

But the next phase will be more complex. As the NEM becomes more renewable-heavy, the gap between annual accounting and real-time supply will matter more. Firming, storage, and transmission strength will increasingly determine reliability—and those are assets the ACT does not control. That means its clean energy future remains closely tied to decisions made in NSW and across the broader grid.

Looking ahead, the ACT’s influence may shift from being a renewable buyer to a renewable shaper. Its policies can encourage firmed contracts, storage-backed generation, and demand-side flexibility that better align with system needs. The territory has already shown what policy can achieve at the consumption level. The challenge now is ensuring that “beyond 100% renewables” also supports a grid that works second by second, not just year by year.

What it means for homeowners

For ACT households, the shift to 100% renewable has changed where energy is sourced, not how electricity behaves at the power point. Homes still rely on the same grid as surrounding NSW regions, which means prices, outages, and reliability are shaped by broader market conditions rather than local generation. The renewable benefit shows up over time through lower emissions and more stable long-term pricing, not through guaranteed clean power at every moment.

Rooftop solar plays a more direct role. Canberra has strong solar uptake, and households that generate during the day can reduce bills and exposure to peak prices. But without large-scale local storage, the value of solar still depends on timing and tariff structures. For most homeowners, the ACT’s model delivers climate certainty first, with financial and reliability benefits flowing indirectly through the wider grid rather than from infrastructure on their doorstep.

Beyond the numbers

The ACT has shown that it’s possible to decarbonise electricity consumption through policy, contracts, and market participation rather than physical infrastructure. In doing so, it has pushed the NEM forward and helped underwrite renewable projects well beyond its borders. But its experience also highlights a hard truth that 100% renewable claim does not remove dependence on a complex, shared grid.

As the energy transition depends, the ACT’s role will be less about reaching new percentages and more about influencing how renewables are firmed, stored, and delivered in real time. Its success has been in proving was policy can achieve. The next test is ensuring that those achievements continue to align with the practical realities of a grid that must balance supply and demand every second.

A different kind of blueprint

The ACT’s electricity story isn’t about turbines, dams, or transmission lines. It’s about how far policy and procurement can go in reshaping a grid that the territory doesn’t physically control. By committing early and consistently to renewable contracts, the ACT has demonstrated that decarbonisation can be driven from the demand side — and that small jurisdictions can have outsized influence.

At the same time, its experience underlines the limits of that approach. A system built on accounting still depends on real infrastructure elsewhere to deliver power when it’s needed. As more regions chase higher renewable targets, the ACT’s model stands as both a proof point and a caution: policy can lead the transition, but physics still sets the boundaries.

Closing the Loop

The ACT has taken renewables further than any other jurisdiction in Australia — not by building more infrastructure, but by changing how electricity is bought, valued, and accounted for. Its success shows what strong policy, long-term planning, and market participation can achieve, even without physical control of the grid.

At the same time, the territory’s experience makes one thing clear: being “beyond 100% renewables” doesn’t remove reliance on a shared system. As the national grid becomes cleaner and more complex, the ACT’s role will be less about setting targets and more about shaping how renewable energy is firmed, balanced, and delivered in real time.

Energy Matters has been in the solar industry since 2005 and has helped over 40,000 Australian households in their journey to energy independence.

Complete our quick Solar Quote Quiz to receive up to 3 FREE solar quotes from trusted local installers – it’ll only take you a few minutes and is completely obligation-free.